Iran insider & UK spy: How a double life ended on gallows – Times of India

In April 2008, a senior British intelligence official flew to Tel Aviv, Israel, to deliver an explosive revelation to his Israeli counterparts: Britain had a mole in Iran with high-level access to the country’s nuclear and defence secrets.

The spy had provided valuable information — and would continue to do so for years — intelligence that would prove critical in eliminating any doubt in Western capitals that Iran was pursuing nuclear weapons and in persuading the world to impose sweeping sanctions against Iran, according to intelligence officials.

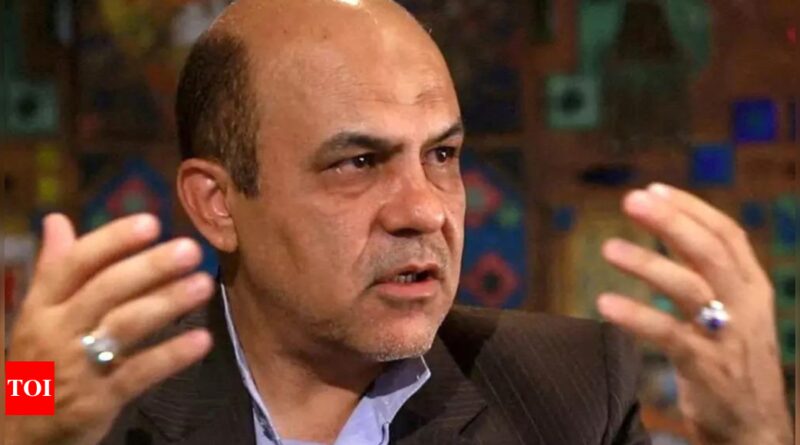

The identity of that spy has long been secret. But on January 11, the execution in Iran of a former deputy defence minister named Alireza Akbari on espionage charges brought to light something that had been hidden for 15 years:

Akbari was the British mole. Akbari had long lived a double life. To the public, he was a religious zealot and political hawk, a senior military commander of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard and a deputy defence minister who later moved to London and went into the private sector but never lost the trust of Iran’s leaders. But in 2004, according to the officials, he began sharing Iran’s nuclear secrets with British intelligence. He appeared to get away with it until 2019, when Iran discovered with the assistance of Russian intelligence officials that he had revealed the existence of a clandestine Iranian nuclear weapons programme deep in the mountains near Tehran, according to two Iranian sources with links to the Revolutionary Guard.

In addition to accusing Akbari of revealing its nuclear and military secrets, Iran has also said he disclosed the identity and activities of more than 100 officials, most significantly Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, the chief nuclear scientist whom Israel assassinated in 2020.

Akbari, who was 62 when he was executed, was an unlikely spy. Akbari, who was born into a conservative middle-class family in the city of Shiraz, was a teenager when the Iranian revolution in 1979 toppled the monarchy and war with Iraq followed, his Mehdi brother said. Inflamed with revolutionary passion, he and an older brother enlisted as soldiers, and by the time he left the front lines almost six years later, he was a decorated commander of the Revolutionary Guard. Returning to civilian life, Akbari ascended the ranks, rising to deputy defence minister and holding advisory positions on the Supreme National Security Council and other government bodies. He forged close relationships with two powerful men: Fakhrizadeh and Ali Shamkhani, head of the council, whom he served as adeputy and an adviser,

In eight short videos aired by state television after his execution, Akbari detailed his spying activities and his recruitment by Britain at a function at the British Embassy in Tehran. But later, in an audio message broadcast by BBC Persian — it had been obtained through his family, Akbari said the confessions were coerced.

In the videos, Akbari said he was recruited in 2004 and was told that he and his family would be given visas for Britain. The next year, he travelled to Britain and met with an MI6 handler, he said. Over the next few years, Akbari said he created front companies in Austria, Spain and Britain to provide cover for meetings with his handlers. Iran has said MI6 paid Akbari nearly $2.4 million. Akbari retired from his official posts in 2008, but continued to serve as adviser to Shamkhani and other officials.

In April 2008, Britain received and shared with Israel and Western agencies the intelligence about Fordo, a uranium enrichment facility deep inside an underground military complex, that was part of Iran’s efforts to build a nuclear bomb. Fordo’s discovery changed the world’s understanding of Iran’s nuclear programme and redrew military and cyberplans for countering it. In September 2009, at a G7 summit, President Barack Obama, along with the leaders of Britain and France, revealed that Fordo was a nuclear enrichment plant. “The discovery of Fordo radically altered the attitude of the international community toward Iran,” said Norman Roule, the former national intelligence manager for Iran at the CIA. He said it helped convince China and Russia that Iran had not been transparent and drove the push for more sanctions. Execution of senior officials is extremely rare in Iran. The last time a senior technocrat was executed was in 1982. Britain has never publicly acknowledged that Akbari, who became a British citizen in 2012, was its spy. But it condemned Tehran for executing Akbari, briefly recalled its ambassador and imposed new sanctions on Iran.

The spy had provided valuable information — and would continue to do so for years — intelligence that would prove critical in eliminating any doubt in Western capitals that Iran was pursuing nuclear weapons and in persuading the world to impose sweeping sanctions against Iran, according to intelligence officials.

The identity of that spy has long been secret. But on January 11, the execution in Iran of a former deputy defence minister named Alireza Akbari on espionage charges brought to light something that had been hidden for 15 years:

Akbari was the British mole. Akbari had long lived a double life. To the public, he was a religious zealot and political hawk, a senior military commander of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard and a deputy defence minister who later moved to London and went into the private sector but never lost the trust of Iran’s leaders. But in 2004, according to the officials, he began sharing Iran’s nuclear secrets with British intelligence. He appeared to get away with it until 2019, when Iran discovered with the assistance of Russian intelligence officials that he had revealed the existence of a clandestine Iranian nuclear weapons programme deep in the mountains near Tehran, according to two Iranian sources with links to the Revolutionary Guard.

In addition to accusing Akbari of revealing its nuclear and military secrets, Iran has also said he disclosed the identity and activities of more than 100 officials, most significantly Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, the chief nuclear scientist whom Israel assassinated in 2020.

Akbari, who was 62 when he was executed, was an unlikely spy. Akbari, who was born into a conservative middle-class family in the city of Shiraz, was a teenager when the Iranian revolution in 1979 toppled the monarchy and war with Iraq followed, his Mehdi brother said. Inflamed with revolutionary passion, he and an older brother enlisted as soldiers, and by the time he left the front lines almost six years later, he was a decorated commander of the Revolutionary Guard. Returning to civilian life, Akbari ascended the ranks, rising to deputy defence minister and holding advisory positions on the Supreme National Security Council and other government bodies. He forged close relationships with two powerful men: Fakhrizadeh and Ali Shamkhani, head of the council, whom he served as adeputy and an adviser,

In eight short videos aired by state television after his execution, Akbari detailed his spying activities and his recruitment by Britain at a function at the British Embassy in Tehran. But later, in an audio message broadcast by BBC Persian — it had been obtained through his family, Akbari said the confessions were coerced.

In the videos, Akbari said he was recruited in 2004 and was told that he and his family would be given visas for Britain. The next year, he travelled to Britain and met with an MI6 handler, he said. Over the next few years, Akbari said he created front companies in Austria, Spain and Britain to provide cover for meetings with his handlers. Iran has said MI6 paid Akbari nearly $2.4 million. Akbari retired from his official posts in 2008, but continued to serve as adviser to Shamkhani and other officials.

In April 2008, Britain received and shared with Israel and Western agencies the intelligence about Fordo, a uranium enrichment facility deep inside an underground military complex, that was part of Iran’s efforts to build a nuclear bomb. Fordo’s discovery changed the world’s understanding of Iran’s nuclear programme and redrew military and cyberplans for countering it. In September 2009, at a G7 summit, President Barack Obama, along with the leaders of Britain and France, revealed that Fordo was a nuclear enrichment plant. “The discovery of Fordo radically altered the attitude of the international community toward Iran,” said Norman Roule, the former national intelligence manager for Iran at the CIA. He said it helped convince China and Russia that Iran had not been transparent and drove the push for more sanctions. Execution of senior officials is extremely rare in Iran. The last time a senior technocrat was executed was in 1982. Britain has never publicly acknowledged that Akbari, who became a British citizen in 2012, was its spy. But it condemned Tehran for executing Akbari, briefly recalled its ambassador and imposed new sanctions on Iran.