“I Was Right”, Biden Gloats About Help From Taliban in Response to State Dept Report Criticizing His Disastrous Afghanistan Retreat | The Gateway Pundit | by Kristinn Taylor | 30

A long withheld State Department report critical of the Biden administration’s handling of the fall of Afghanistan in 2021 was finally released on the Friday before the long Fourth of July holiday weekend.

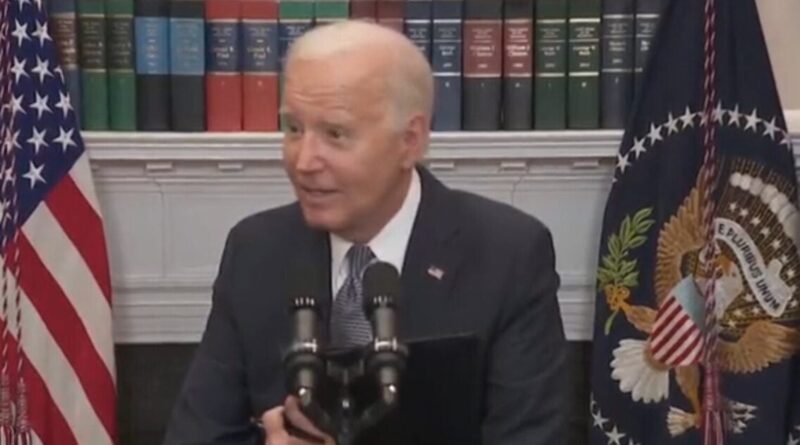

“I was right”, Biden gloated to a reporter about Afghanistan on Friday, pool video screen image.

Among several flawed decisions and lack of leadership cited, the report criticized Biden’s decision to withdraw U.S. troops and abandon the Bagram Air Base as hurting the effort to facilitate the non-noncombatant evacuation operation (NEO) and secure the large embassy in Kabul. The report also was critical of the Trump administration, however Biden was president for eight months and his actions precipitated the sudden fall of Kabul. A key problem for the State Department was that a pre-planned staff rotation took place at the Kabul embassy at the end of July/early August 2021 even as Afghanistan was on the brink.

13 U.S. servicemembers and over 150 Afghans were killed in a terrorist bombing at the Kabul airport during the U.S. evacuations on August 26,2021. About 125,000 people, including 6,000 American were evacuated by the U.S., with many more left behind, in the chaotic Kabul airport operation. Afghanistan has returned to the pre-U.S. days of subjugation by the Islamist Taliban government with women losing almost all rights and being denied higher education.

Asked by a reporter on Friday about the report, Biden gloated that he had gotten help from the Taliban, “Remember what I said about Afghanistan? I said al-Qaeda would not be there. I said it wouldn’t be there. I said we’d get help from the Taliban. What’s happening now? What’s going on? Read your press. I was right.”

Biden on his disastrous Afghanistan withdrawal: “I was right”

Biden promised a safe and orderly withdrawal and that it was “highly unlikely” the Taliban would take over Afghanistan. Instead, there was absolute chaos, the Taliban took over, and 13 servicemembers were killed. pic.twitter.com/7fDgsmvMZy

— RNC Research (@RNCResearch) June 30, 2023

Excerpts from the unclassified version of the State Department report.

FINDINGS

In examining the Department of State’s efforts between January 2020 and August 2021 related to the process of ending the U.S. military mission in Afghanistan, the After Action Review (AAR) team determined the following:

Planning for the Military Withdrawal

1. The decisions of both President Trump and President Biden to end the U.S. military mission in Afghanistan had serious consequences for the viability of the Afghan government and its security. Those decisions are beyond the scope of this review, but the AAR team found that during both administrations there was insufficient senior-level consideration of worst-case scenarios and how quickly those might follow.

2. For the Department, the end to the U.S. military mission presented an enormous challenge as it sought to mitigate the loss of “key enablers” that the military had provided and maintain a diplomatic and assistance presence in Afghanistan in accordance with the stated intent of both administrations. Some officials questioned how and whether the Department could sufficiently mitigate the loss of military support, and the Bureau of Diplomatic Security (DS) warned of the level of risk that the Department would be accepting.

3. Even prior to the signing of the February 2020 U.S.-Taliban Agreement, President Trump had signaled his desire to end the U.S. military presence in Afghanistan, and he steadily withdrew U.S. forces following that agreement. When the Trump administration left office, key questions remained unanswered about how the United States would meet the May 2021 deadline for a full military withdrawal, how the United States could maintain a diplomatic presence in Kabul after that withdrawal, and what might happen to those eligible for the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) program as well as other at-risk Afghans.

4. Following President Biden’s decision in April 2021 to proceed with the withdrawal of U.S. forces under a new deadline of September 11, the U.S. military moved swiftly with the retrograde to protect U.S. forces, but the speed of that retrograde compounded the difficulties the Department faced in mitigating the loss of the military’s key enablers. Critically, the decision to hand over Bagram Air Base to the Afghan government meant that Hamid Karzai International Airport (HKIA) would be the only avenue for a possible noncombatant evacuation operation (NEO).

5. Due to the enormous challenge of providing security for the large diplomatic mission in a conflict area, there was a plan to retain some U.S. forces to provide critical security, but the details of that – and what stay-behind force the Taliban would accept as consistent with the February 2020 U.S.-Taliban Agreement – had not been clearly established by the time Kabul fell to the Taliban in August 2021.

Pre-Crisis Contingency Planning and Execution

6. Ultimately, the Department’s ability to maintain an embassy depended on the overall security environment in Kabul and the ability of the Afghan government to help protect foreign diplomats. For this reason, Embassy Kabul and the Department prepared a number of contingency plans, ranging from a further reduction in personnel, to a temporary relocation to HKIA, to a complete closure of the embassy.

7. The Department placed Embassy Kabul on ordered departure (OD) status at the end of April in the wake of President Biden’s decision, but that did not result in a notable immediate reduction of the embassy’s footprint (most of which involved security and life support) in part because of the need to take on additional roles and responsibilities given the withdrawal of the U.S. military.

8. While predictions varied, up until almost the time Kabul fell, most estimates were that the Afghan government and its forces could hold the city for weeks, if not months. That said, as security conditions in Afghanistan deteriorated, some argued for more urgency in planning for a possible collapse.

9. U.S. military planning for a possible NEO had been underway with post for some time, but the Department’s participation in the NEO planning process was hindered by the fact that it was unclear who in the Department had the lead. Coordination with DoD worked better on the ground in Kabul.

10. A major challenge facing NEO planning was determining the scale and scope of the operation, especially when it came to how many at-risk Afghan nationals would be included, how they would be prioritized, and how long their evacuation might take. Senior administration officials had not made clear decisions regarding the universe of at-risk Afghans who would be included by the time the operation started nor had they determined where those Afghans would be taken. That added significantly to the challenges the Department and DoD faced during the evacuation.

11. Crisis preparation and planning were inhibited to a degree by concerns about the signals that might be sent, especially anything that might suggest the United States had lost confidence in the Afghan government and thus contribute to its collapse. However, the AAR notes that once it got underway, the plan for closing the embassy compound and evacuating U.S. government personnel and U.S. citizen and third-country contractors proceeded well, considering the speed at which it was implemented.

Crisis Operations

16. Embassy Kabul and TDY Department personnel performed heroically under dangerous and difficult conditions at HKIA to help evacuate tens of thousands of U.S. citizens, legal permanent residents, locally employed staff, and at-risk Afghans from Afghanistan after Kabul fell to the Taliban. Their work is a credit to the Department and the American people.

17. Although the Department had established the ACTF, it failed to establish a broader task force as the situation in Afghanistan deteriorated in late July and early August 2021. Establishing such a task force earlier would have brought key players together to address issues related to a possible NEO.

18. Naming a 7th Floor principal to oversee all elements of the crisis response would have improved coordination across different lines of effort.

19. The complicated Department task force structure that was created when the evacuation began proved confusing to many participants, and knowledge management and communication among and across various lines of effort was problematic. It did not help that various task force entities were physically scattered throughout the Department. Consistently staffing the task forces with experienced people during a pandemic also proved challenging.

23. Most important, the Department proved unable to buffer those on the ground in Kabul from receiving multiple, direct calls and messages from current or former senior officials, members of Congress, and/or prominent private citizens asking and in some cases demanding that they provide assistance to specific at-risk Afghans. Responding to such demands often placed Department employees at even greater risk and hindered the effort to move larger groups of people out.

24. Constantly changing policy guidance and public messaging from Washington regarding which populations were eligible for relocation and how the embassy should manage outreach and flow added to the confusion and often failed to take into account key facts on the ground.